This blog was originally published by Alessandro Carminati, Principal Software Engineer at Red Hat, on his personal blog and is republished here with permission.

Why I Went Down This Rabbit Hole

Back in 1993, when Linux 0.99.14 was released, /dev/mem made perfect sense. Computers were simpler, physical memory was measured in megabytes, and security basically boiled down to: “Don’t run untrusted programs.”

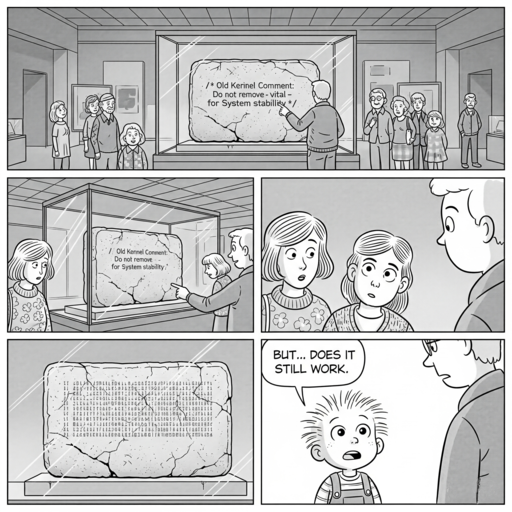

Fast-forward to today. We have gigabytes (or terabytes!) of RAM, multi-layered virtualization, and strict security requirements… And /dev/mem is still here, quietly sitting in the kernel, practically unchanged… A fossil from a different era. It’s incredibly powerful, terrifyingly dangerous, and absolutely fascinating.

My work on /dev/mem is part of a bigger effort by the ELISA Architecture working group, whose mission is to improve Linux kernel documentation and testing. This project is a small pilot in a broader campaign: build tests for old, fundamental pieces of the kernel that everyone depends on but few dare to touch.

In a previous blog post, “When kernel comments get weird”, I dug into the /dev/mem source code and traced its history, uncovering quirky comments and code paths that date back decades. That post was about exploration. This one is about action: turning that historical understanding into concrete tests to verify that /dev/mem behaves correctly… Without crashing the very systems those tests run on.

What /dev/mem Is and Why It Matters

/dev/mem is a character device that exposes physical memory directly to userspace. Open it like a file, and you can read or write raw physical addresses: no page tables, no virtual memory abstractions, just the real thing.

Why is this powerful? Because it lets you:

- Peek at firmware data structures,

- Poke device registers directly,

- Explore memory layouts normally hidden from userspace.

It’s like being handed the keys to the kingdom… and also a grenade, with the pin halfway pulled.

A single careless write to /dev/mem can:

- Crash the kernel,

- Corrupt hardware state,

- Or make your computer behave like a very expensive paperweight.

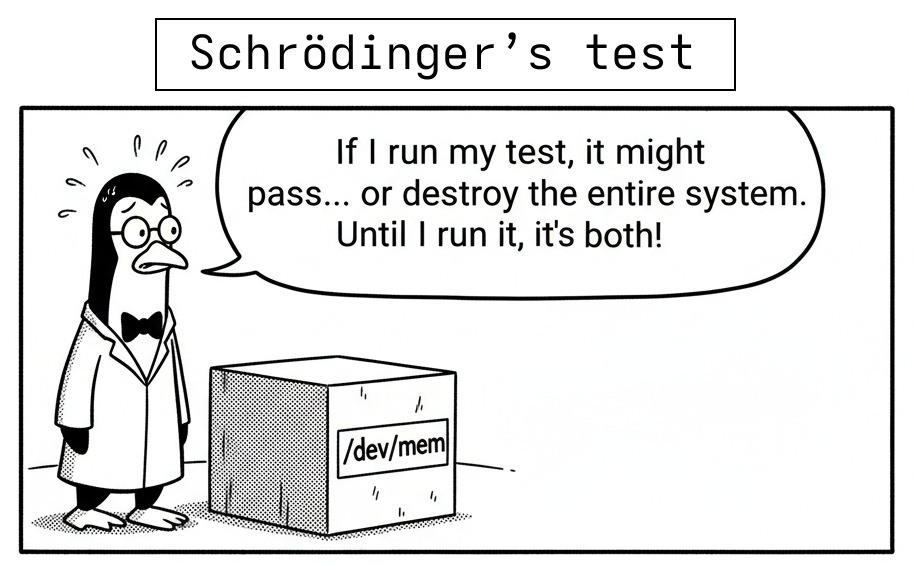

For me, that danger is exactly why this project matters. Testing /dev/mem itself is tricky: the tests must prove the driver works, without accidentally nuking the machine they run on.

STRICT_DEVMEM and Real-Mode Legacy

One of the first landmines you encounter with /dev/mem is the kernel configuration option STRICT_DEVMEM.

Think of it as a global policy switch:

- If disabled,

/dev/memlets privileged userspace access almost any physical address: kernel RAM, device registers, firmware areas, you name it. - If enabled, the kernel filters which physical ranges are accessible through

/dev/mem. Typically, it only permits access to low legacy regions, like the first megabyte of memory where real-mode BIOS and firmware tables traditionally live, while blocking everything else.

Why does this matter? Some very old software, like emulators for DOS or BIOS tools, still expects to peek and poke those legacy addresses as if running on bare metal. STRICT_DEVMEM exists so those programs can still work: but without giving them carte blanche access to all memory.

So when you’re testing /dev/mem, the presence (or absence) of STRICT_DEVMEM completely changes what your test can do. With it disabled, /dev/mem is a wild west. With it enabled, only a small, carefully whitelisted subset of memory is exposed.

A Quick Note on Architecture Differences

While /dev/mem always exposes what the kernel considers physical memory, the definition of physical itself can differ across architectures. For example, on x86, physical addresses are the real hardware addresses. On aarch64 with virtualization or secure firmware, EL1 may only see a subset of memory through a translated view, controlled by EL2 or EL3.

The main function that the STRICT_DEVMEM kernel configuration option provides in Linux is to filter and restrict access to physical memory addresses via /dev/mem. It controls which physical address ranges can be legitimately accessed from userspace by helping implement architecture-specific rules to prevent unsafe or insecure memory accesses.

32-Bit Systems and the Mystery of High Memory

On most systems, the kernel needs a direct way to access physical memory. To make that fast, it keeps a linear mapping: a simple, one-to-one correspondence between physical addresses and a range of kernel virtual addresses. If the kernel wants to read physical address 0x00100000, it just uses a fixed offset, like PAGE_OFFSET + 0x00100000. Easy and efficient.

But there’s a catch on 32-bit kernels: The kernel’s entire virtual address space is only 4 GB, and it has to share that with userspace. By convention, 3 GB is given to userspace, and 1 GB is reserved for the kernel, which includes its linear mapping.

Now here comes the tricky part: Physical RAM can easily exceed 1 GB. The kernel can’t linearly map all of it: there just isn’t enough virtual address space.

The extra memory beyond the first gigabyte is called highmem (short for high memory). Unlike the low 1 GB, which is always mapped, highmem pages are mapped temporarily, on demand, whenever the kernel needs them.

Why this matters for /dev/mem: /dev/mem depends on the permanent linear mapping to expose physical addresses. Highmem pages aren’t permanently mapped, so /dev/mem simply cannot see them. If you try to read those addresses, you’ll get zeros or an error, not because /dev/mem is broken, but because that part of memory is literally invisible to it.

For testing, this introduces extra complexity:

- Some reads may succeed on lowmem addresses but fail on highmem.

- Behavior on a 32-bit machine with highmem is fundamentally different from a 64-bit system, where all RAM is flat-mapped and visible.

Highmem is a deep topic that deserves its own article, but even this quick overview is enough to understand why it complicates /dev/mem testing.

How Reads and Writes Actually Happen

A common misconception is that a single userspace read() or write() call maps to one atomic access to the underlaying block device. In reality, the VFS layer and the device driver may split your request into multiple chunks, depending on alignment and boundaries, in this case.

Why does this happen?

- Many devices can only handle fixed-size or aligned operations.

- For physical memory, the natural unit is a page (commonly 4 KB).

When your request crosses a page boundary, the kernel internally slices it into:

- A first piece up to the page boundary,

- Several full pages,

- A trailing partial page.

For /dev/mem, this is a crucial detail: A single read or write might look seamless from userspace, but under the hood it’s actually several smaller operations, each with its own state. If the driver mishandles even one of them, you could see skipped bytes, duplicated data, or mysterious corruption.

Understanding this behavior is key to writing meaningful tests.

Safely Reading and Writing Physical Memory

At this point, we know what /dev/mem is and why it’s both powerful and terrifying. Now we’ll move to the practical side: how to interact with it safely, without accidentally corrupting your machine or testing in meaningless ways.

My very first test implementation kept things simple:

- Only small reads or writes,

- Always staying within a single physical page,

- Never crossing dangerous boundaries.

Even with these restrictions, /dev/mem testing turned out to be more like diffusing a bomb than flipping a switch.

Why “success” doesn’t mean success (in this very specific case)

Normally, when you call a syscall like read() or write(), you can safely assume the kernel did exactly what you asked. If read() returns a positive number, you trust that the data in your buffer matches the file’s contents. That’s the contract between userspace and the kernel, and it works beautifully in everyday programming.

But here’s the catch: We’re not just using /dev/mem; we’re testing whether /dev/mem itself works correctly.

This changes everything.

If my test reads from /dev/mem and fills a buffer with data, I can’t assume that data is correct:

- Maybe the driver returned garbage,

- Maybe it skipped a region or duplicated bytes,

- Maybe it silently failed in the middle but still updated the counters.

The same goes for writes: A return code of “success” doesn’t guarantee the write went where it was supposed to, only that the driver finished running without errors.

So in this very specific context, “success” doesn’t mean success. I need independent ways to verify the result, because the thing I’m testing is the thing that would normally be trusted.

Finding safe places to test: /proc/iomem

Before even thinking about reading or writing physical memory, I need to answer one critical question:

“Which parts of physical memory are safe to touch?”

If I just pick a random address and start writing, I could:

- Overwrite the kernel’s own code,

- Corrupt a driver’s I/O-mapped memory,

- Trash ACPI tables that the system kernel depends on,

- Or bring the whole machine down in spectacular fashion.

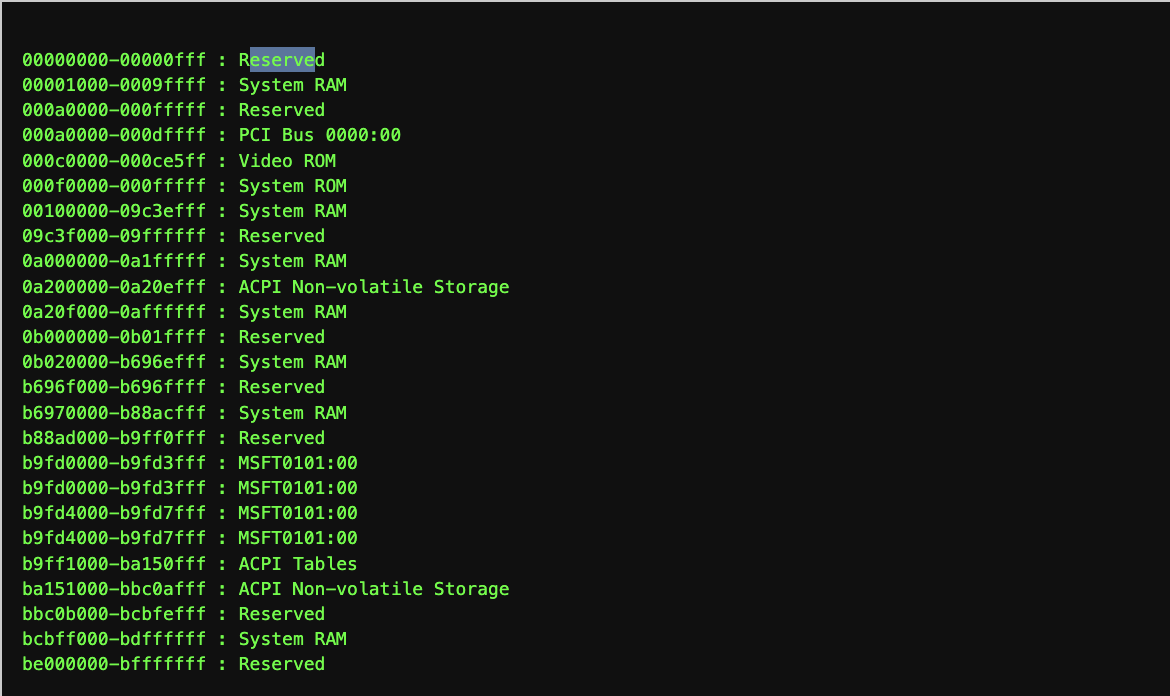

This is where /proc/iomem comes to the rescue. It’s a text file that maps out how the physical address space is currently being used. Each line describes a range of physical addresses and what they’re assigned to.

Here’s a small example:

By parsing /proc/iomem, my test program can:

- Identify which physical regions are safe to work with (like RAM already allocated to my process),

- Avoid regions that are reserved for hardware or critical firmware,

- Adapt dynamically to different machines and configurations.

This is especially important for multi-architecture support. While examples here often look like x86 (because /dev/mem has a long history there), the concept of mapping I/O regions isn’t x86-specific. On ARM, RISC-V, or others, you’ll see different labels… But the principle remains exactly the same.

In short: /proc/iomem is your treasure map, and the first rule of treasure hunting is “don’t blow up the ship while digging for gold.”

The Problem of Contiguous Physical Pages

Up to this point, my work focused on single-page operations. I wasn’t hand-picking physical addresses or trying to be clever about where memory came from. Instead, the process was simple and safe:

- Allocate a buffer in userspace, using

mmap()so it’s page-aligned, - Touch the page to make sure the kernel really backs it with physical memory,

- Walk

/proc/self/pagemapto trace which physical pages back the virtual address in the buffer.

This gives me full visibility into how my userspace memory maps to physical memory. Since the buffer was created through normal allocation, it’s mine to play with, there’s no risk of trampling over the kernel or other userspace processes.

This worked beautifully for basic tests:

- Pick a single page in the buffer,

- Run a tiny read/write cycle through

/dev/mem, - Verify the result,

- Nothing explodes.

But then came the next challenge: What if a read or write crosses a physical page boundary?

Why boundaries matter

The Linux VFS layer doesn’t treat a read or write syscall as one giant, indivisible action. Instead, it splits large operations into chunks, moving through pages one at a time.

For example:

- I request 10 KB from

/dev/mem, - The first 4 KB comes from physical page A,

- The next 4 KB comes from physical page B,

- The last 2 KB comes from physical page C.

If the driver mishandles the transition between pages, I’d never notice unless my test forces it to cross that boundary. It’s like testing a car by only driving in a straight line: Everything looks fine… Until you try to turn the wheel.

To properly test /dev/mem, I need a buffer backed by at least two physically contiguous pages. That way, a single read or write naturally crosses from one physical page into the next… exactly the kind of situation where subtle bugs might hide.

And that’s when the real nightmare began.

Why this is so difficult

At first, this seemed easy. I thought:

“How hard can it be? Just allocate a buffer big enough, like 128 KB, and somewhere inside it, there must be two contiguous physical pages.”

Ah, the sweet summer child optimism. The harsh truth: modern kernels actively work against this happening by accident. It’s not because the kernel hates me personally (though it sure felt like it). It’s because of its duty to prevent memory fragmentation.

When you call brk() or mmap(), the kernel:

- Uses a buddy allocator to manage blocks of physical pages,

- Actively spreads allocations apart to keep them tidy,

- Reserves contiguous ranges for things like hugepages or DMA.

From the kernel’s point of view:

- This keeps the system stable,

- Prevents large allocations from failing later,

- And generally makes life good for everyone.

From my point of view? It’s like trying to find two matching socks in a dryer while it is drying them.

Playing the allocation lottery

My first approach was simple: keep trying until luck strikes.

- Allocate a 128 KB buffer,

- Walk

/proc/self/pagemapto see where all pages landed physically, - If no two contiguous pages are found, free it and try again.

Statistically, this should work eventually. In reality? After thousands of iterations, I’d still end up empty-handed. It felt like buying lottery tickets and never even winning a free one.

The kernel’s buddy allocator is very good at avoiding fragmentation. Two consecutive physical pages are far rarer than you’d think, and that’s by design.

Trying to confuse the allocator

Naturally, my next thought was:

“If the allocator is too clever, let’s mess with it!”

So I wrote a perturbation routine:

- Allocate a pile of small blocks,

- Touch them so they’re actually backed by physical pages,

- Free them in random order to create “holes.”

The hope was to trick the allocator into giving me contiguous pages next time. The result? It sometimes worked, but unpredictably. 4k attempts gave me >80% success. Not reliable enough for a test suite where failures must mean a broken driver, not a grumpy kernel allocator.

The options I didn’t want

There are sure-fire ways to get contiguous pages:

- Writing a kernel module and calling

alloc_pages(). - Using hugepages.

- Configuring CMA regions at boot.

But all of these require special setup or kernel cooperation. My goal was a pure userspace test, so they were off the table.

A new perspective: software MMU

Finally, I relaxed my original requirement. Instead of demanding two pages that are both physically and virtually contiguous, I only needed them to be physically contiguous somewhere in the buffer.

From there, I could build a tiny software MMU:

- Find a contiguous physical pair using

/proc/self/pagemap, - Expose them through a simple linear interface,

- Run the test as if they were virtually contiguous.

This doesn’t eliminate the challenge, but it makes it practical. No kernel hacks, no special boot setup, just a bit of clever user-space logic.

From Theory to Test Code

All this theory eventually turned into a real test tool, because staring at /proc/self/pagemap is fun… but only for a while. The test lives here:

github.com/alessandrocarminati/devmem_test

It’s currently packaged as a Buildroot module, which makes it easy to run on different kernels and architectures without messing up your main system. The long-term goal is to integrate it into the kernel’s selftests framework, so these checks can run as part of the regular Linux testing pipeline. For now, it’s a standalone sandbox where you can:

- Experiment with

/dev/memsafely (on a test machine!), - Play with

/proc/self/pagemapand see how virtual pages map to physical memory, - Try out the software MMU idea without needing kernel modifications.

And expect it still work in progress.

Elektrobit has been an active contributor to the ELISA Project for several years, and Simone’s appointment reflects the company’s commitment to advancing the use of open source technologies in industries such as automotive, industrial, medical, and beyond.

Elektrobit has been an active contributor to the ELISA Project for several years, and Simone’s appointment reflects the company’s commitment to advancing the use of open source technologies in industries such as automotive, industrial, medical, and beyond.