This blog is written by Alessandro Carminati, Principal Software Engineer at Red Hat and lead for the ELISA Project’s Linux Features for Safety-Critical Systems (LFSCS) WG.

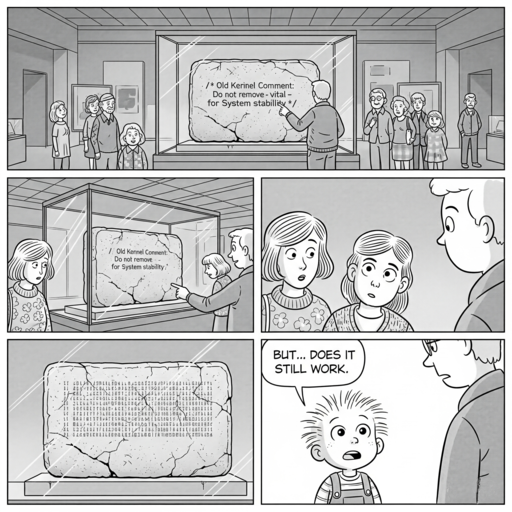

As part of the ELISA community, we spend a good chunk of our time spelunking through the Linux kernel codebase. It’s like code archeology: you don’t always find treasure, but you _do_ find lots of comments left behind by developers from the ’90s that make you go, “Wait… really?”

One of the ideas we’ve been chasing is to make kernel comments a bit smarter: not only human-readable, but also machine-readable. Imagine comments that could be turned into tests, so they’re always checked against reality. Less “code poetry from 1993”, more “living documentation”.

Speaking of code poetry, [here] one gem we stumbled across in `mem.c`:

``` /* The memory devices use the full 32/64 bits of the offset, * and so we cannot check against negative addresses: they are ok. * The return value is weird, though, in that case (0). */ ```

This beauty has been hanging around since **Linux 0.99.14**… back when Bill Clinton was still president-elect, “Mosaic” was the hot new browser,

and PDP-11 was still produced and sold.

Back then, it made sense, and reflected exactley what the code did.

Fast-forward thirty years, and the comment still kind of applies…

but mostly in obscure corners of the architecture zoo.

On the CPUs people actually use every day?

```

$ cat lseek.asm

BITS 64

%define SYS_read 0

%define SYS_write 1

%define SYS_open 2

%define SYS_lseek 8

%define SYS_exit 60

; flags

%define O_RDONLY 0

%define SEEK_SET 0

section .data

path: db "/dev/mem",0

section .bss

align 8

buf: resq 1

section .text

global _start

_start:

mov rax, SYS_open

lea rdi, [rel path]

xor esi, esi

xor edx, edx

syscall

mov r12, rax ; save fd in r12

mov rax, SYS_lseek

mov rdi, r12

mov rsi, 0x8000000000000001

xor edx, edx

syscall

mov [rel buf], rax

mov rax, SYS_write

mov edi, 1

lea rsi, [rel buf]

mov edx, 8

syscall

mov rax, SYS_exit

xor edi, edi

syscall

$ nasm -f elf64 lseek.asm -o lseek.o

$ ld lseek.o -o lseek

$ sudo ./lseek| hexdump -C

00000000 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 80 |........|

00000008

$ # this is not what I expect, let's double check

$ sudo gdb ./lseek

GNU gdb (Fedora Linux) 16.3-1.fc42

Copyright (C) 2024 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

License GPLv3+: GNU GPL version 3 or later <http://gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html>

This is free software: you are free to change and redistribute it.

There is NO WARRANTY, to the extent permitted by law.

Type "show copying" and "show warranty" for details.

This GDB was configured as "x86_64-redhat-linux-gnu".

Type "show configuration" for configuration details.

For bug reporting instructions, please see:

<https://www.gnu.org/software/gdb/bugs/>.

Find the GDB manual and other documentation resources online at:

<http://www.gnu.org/software/gdb/documentation/>.

For help, type "help".

Type "apropos word" to search for commands related to "word"...

Reading symbols from ./lseek...

(No debugging symbols found in ./lseek)

(gdb) b _start

Breakpoint 1 at 0x4000b0

(gdb) r

Starting program: /tmp/lseek

Breakpoint 1, 0x00000000004000b0 in _start ()

(gdb) x/30i $pc

=> 0x4000b0 <_start>: mov $0x2,%eax

0x4000b5 <_start+5>: lea 0xf44(%rip),%rdi # 0x401000

0x4000bc <_start+12>: xor %esi,%esi

0x4000be <_start+14>: xor %edx,%edx

0x4000c0 <_start+16>: syscall

0x4000c2 <_start+18>: mov %rax,%r12

0x4000c5 <_start+21>: mov $0x8,%eax

0x4000ca <_start+26>: mov %r12,%rdi

0x4000cd <_start+29>: movabs $0x8000000000000001,%rsi

0x4000d7 <_start+39>: xor %edx,%edx

0x4000d9 <_start+41>: syscall

0x4000db <_start+43>: mov %rax,0xf2e(%rip) # 0x401010

0x4000e2 <_start+50>: mov $0x1,%eax

0x4000e7 <_start+55>: mov $0x1,%edi

0x4000ec <_start+60>: lea 0xf1d(%rip),%rsi # 0x401010

0x4000f3 <_start+67>: mov $0x8,%edx

0x4000f8 <_start+72>: syscall

0x4000fa <_start+74>: mov $0x3c,%eax

0x4000ff <_start+79>: xor %edi,%edi

0x400101 <_start+81>: syscall

0x400103: add %al,(%rax)

0x400105: add %al,(%rax)

0x400107: add %al,(%rax)

0x400109: add %al,(%rax)

0x40010b: add %al,(%rax)

0x40010d: add %al,(%rax)

0x40010f: add %al,(%rax)

0x400111: add %al,(%rax)

0x400113: add %al,(%rax)

0x400115: add %al,(%rax)

(gdb) b *0x4000c2

Breakpoint 2 at 0x4000c2

(gdb) b *0x4000db

Breakpoint 3 at 0x4000db

(gdb) c

Continuing.

Breakpoint 2, 0x00000000004000c2 in _start ()

(gdb) i r

rax 0x3 3

rbx 0x0 0

rcx 0x4000c2 4194498

rdx 0x0 0

rsi 0x0 0

rdi 0x401000 4198400

rbp 0x0 0x0

rsp 0x7fffffffe3a0 0x7fffffffe3a0

r8 0x0 0

r9 0x0 0

r10 0x0 0

r11 0x246 582

r12 0x0 0

r13 0x0 0

r14 0x0 0

r15 0x0 0

rip 0x4000c2 0x4000c2 <_start+18>

eflags 0x246 [ PF ZF IF ]

cs 0x33 51

ss 0x2b 43

ds 0x0 0

es 0x0 0

fs 0x0 0

gs 0x0 0

fs_base 0x0 0

gs_base 0x0 0

(gdb) # fd is just fine rax=3 as expected.

(gdb) c

Continuing.

Breakpoint 3, 0x00000000004000db in _start ()

(gdb) i r

rax 0x8000000000000001 -9223372036854775807

rbx 0x0 0

rcx 0x4000db 4194523

rdx 0x0 0

rsi 0x8000000000000001 -9223372036854775807

rdi 0x3 3

rbp 0x0 0x0

rsp 0x7fffffffe3a0 0x7fffffffe3a0

r8 0x0 0

r9 0x0 0

r10 0x0 0

r11 0x246 582

r12 0x3 3

r13 0x0 0

r14 0x0 0

r15 0x0 0

rip 0x4000db 0x4000db <_start+43>

eflags 0x246 [ PF ZF IF ]

cs 0x33 51

ss 0x2b 43

ds 0x0 0

es 0x0 0

fs 0x0 0

gs 0x0 0

fs_base 0x0 0

gs_base 0x0 0

(gdb) # According to that comment, rax should have been 0, but it is not.

(gdb) c

Continuing.

�[Inferior 1 (process 186746) exited normally]

(gdb)

```

Not so much. Seeking at `0x8000000000000001`…

Returns `0x8000000000000001` not `0` as anticipated in the comment.

We’re basically facing the kernel version of that “Under Construction”

GIF on websites from the 90s, still there, but mostly just nostalgic

decoration now.

## The Mysterious Line in `read_mem`

Let’s zoom in on one particular bit of code in [`read_mem`](https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v6.17-rc2/source/drivers/char/mem.c#L82):

``` phys_addr_t p = *ppos; /* ... other code ... */ if (p != *ppos) return 0; ```

At first glance, this looks like a no-op; why would `p` be different from

`*ppos` when you just copied it?

It’s like testing if gravity still works by dropping your phone…

**spoiler: it does.**

But as usual with kernel code, the weirdness has a reason.

## The Problem: Truncation on 32-bit Systems

Here’s what’s going on:

– `*ppos` is a `loff_t`, which is a 64-bit signed integer.

– `p` is a `phys_addr_t`, which holds a physical address.

On a 64-bit system, both are 64 bits wide. Assignment is clean, the check

always fails (and compilers just toss it out).

But on a 32-bit system, `phys_addr_t` is only 32 bits. Assign a big 64-bit

offset to it, and **boom**, the top half vanishes.

Truncated, like your favorite TV series canceled after season 1.

That `if (p != *ppos)` check is the safety net.

It spots when truncation happens and bails out early, instead of letting

some unlucky app read from la-la land.

## Assembly Time: 64-bit vs. 32-bit

On 64-bit builds (say, AArch64), the compiler optimizes away the check.

``` ┌ 736: sym.read_mem (int64_t arg2, int64_t arg3, int64_t arg4); │ `- args(x1, x2, x3) vars(13:sp[0x8..0x70]) │ 0x08000b10 1f2003d5 nop │ 0x08000b14 1f2003d5 nop │ 0x08000b18 3f2303d5 paciasp │ 0x08000b1c fd7bb9a9 stp x29, x30, [sp, -0x70]! │ 0x08000b20 fd030091 mov x29, sp │ 0x08000b24 f35301a9 stp x19, x20, [var_10h] │ 0x08000b28 f40301aa mov x20, x1 │ 0x08000b2c f55b02a9 stp x21, x22, [var_20h] │ 0x08000b30 f30302aa mov x19, x2 │ 0x08000b34 750040f9 ldr x21, [x3] │ 0x08000b38 e10302aa mov x1, x2 │ 0x08000b3c e33700f9 str x3, [var_68h] ; phys_addr_t p = *ppos; │ 0x08000b40 e00315aa mov x0, x21 │ 0x08000b44 00000094 bl valid_phys_addr_range │ ┌─< 0x08000b48 40150034 cbz w0, 0x8000df0 ;if (!valid_phys_addr_range(p, count)) │ │ 0x08000b4c 00000090 adrp x0, segment.ehdr │ │ 0x08000b50 020082d2 mov x2, 0x1000 │ │ 0x08000b54 000040f9 ldr x0, [x0] │ │ 0x08000b58 01988152 mov w1, 0xcc0 │ │ 0x08000b5c f76303a9 stp x23, x24, [var_30h] [...] ``` Nothing to see here, move along. But on 32-bit builds (like old-school i386), the check shows up loud and proud in the assembly. ``` [0x080003e0]> pdf ┌ 392: sym.read_mem (int32_t arg_8h); │ `- args(sp[0x4..0x4]) vars(5:sp[0x14..0x24]) │ 0x080003e0 55 push ebp │ 0x080003e1 89e5 mov ebp, esp │ 0x080003e3 57 push edi │ 0x080003e4 56 push esi │ 0x080003e5 53 push ebx │ 0x080003e6 83ec14 sub esp, 0x14 │ 0x080003e9 8955f0 mov dword [var_10h], edx │ 0x080003ec 8b5d08 mov ebx, dword [arg_8h] │ 0x080003ef c745ec0000.. mov dword [var_14h], 0 │ 0x080003f6 8b4304 mov eax, dword [ebx + 4] │ 0x080003f9 8b33 mov esi, dword [ebx] ; phys_addr_t p = *ppos; │ 0x080003fb 85c0 test eax, eax │ ┌─< 0x080003fd 7411 je 0x8000410 ; if (!valid_phys_addr_range(p, count)) │ ┌┌──> 0x080003ff 8b45ec mov eax, dword [var_14h] │ ╎╎│ 0x08000402 83c414 add esp, 0x14 │ ╎╎│ 0x08000405 5b pop ebx │ ╎╎│ 0x08000406 5e pop esi │ ╎╎│ 0x08000407 5f pop edi │ ╎╎│ 0x08000408 5d pop ebp │ ╎╎│ 0x08000409 c3 ret [...] ```

The CPU literally does a compare-and-jump to enforce it. So yes, this is a _real_ guard, not some leftover fluff.

## Return Value Oddities

Now, here’s where things get even funnier. If the check fails in `read_mem`, the function returns `0`. That’s “no bytes read”, which in file I/O land is totally fine.

But in the twin function `write_mem`, the same situation returns `-EFAULT`. That’s kernel-speak for “Nope, invalid address, stop poking me”.

So, reading from a bad address? You get a polite shrug. Writing to it? You get a slap on the wrist. Fair enough, writing garbage into memory is way more dangerous than failing to read it. Come on, probably here we need to fix things up.

Wrapping It Up

This little dive shows how a single “weird” line of code carries decades of context, architecture quirks, type definitions, and evolving assumptions.

It also shows why comments like the one from 0.99.14 are dangerous: they freeze a moment in time, but reality keeps moving.

Our mission in Elisa Architecture WG is to bring comments back to life: keep them up-to-date, tie them to tests, and make sure they still tell the truth. Because otherwise, thirty years later, we’re all squinting at a line saying “the return value is weird though” and wondering if the developer was talking about code… or just their day.

And now, a brief word from our *sponsors* (a.k.a. me in a different hat): When I’m not digging up ancient kernel comments with the Architecture WG, I’m also leading the Linux Features for Safety-Critical Systems (LFSCS) WG. We’re cooking up some pretty exciting stuff there too.

So if you enjoy the kind of archaeology/renovation work we’re doing there, come check out LFSCS as well: same Linux, different adventure.